Nellie Melba

Dame Nellie Melba GBE (19 May 1861 – 23 February 1931), born Helen Porter Mitchell, was an Australian opera soprano. She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian Era and the early 20th century due to the purity of her lyrical voice and the brilliance of her technique. Melba was the first Australian to achieve international recognition as a classical musician. She and May Whitty were the first stage performers to be granted damehoods of the Order of the British Empire.

Contents |

Family and Relationships

Melba was born at Doonside in Richmond, Victoria to a musical family, attending the prestigious Presbyterian Ladies' College, where her musical talent emerged.[1] Her birth certificate lists her parents, David and Isabella Mitchell, as former residents of Forfarshire, Scotland. This ties in with local legend which states that, prior to moving to Australia, her parents lived in what is now a ruined cottage in the valley below the farm of "Glackburn" in Glen Prosen, Angus. (The County of Angus was formerly known as Forfarshire.) Melba lost her mother and a sister in 1880 when she was 19 and she moved with her father David Mitchell to run a sugar mill in Mackay, Queensland in the same year.[1]

There, in 1882, she met Charles Nisbett Frederick Armstrong, a baronet's son three years older than herself, who managed a property near Mackay, Queensland, at the manse of the Ann Street Presbyterian Church in Brisbane.[1][2] They were married shortly after, in the December of the same year. They had one son named George. The marriage swiftly ran into trouble. Melba found herself musically and socially stifled in the marital home: frequent rain kept her house-bound, the humid climate provoked rot in the piano, and her husband "did all he could to halt her progress".[3] On 19 January 1884 she escaped back to Melbourne, and began working on her career. She and Armstrong did attempt to maintain their relationship for a time - he accompanied her to Europe - but he became bored and joined the British army; reluctant to give up the marriage altogether, he continued to make occasional visits to Melba and their son, but after a particularly venomous argument at the time of Melba's Brussels debut in 1887, they both effectively regarded the marriage as over.

In the early 1890s, a scandal occurred after the news of her affair with Philippe, Duke of Orleans, the heir of the Bourbon pretender to the French throne, became public. Having met in England in 1890, the pair had swiftly embarked on a affair. They were seen frequently together in London, which excited some gossip, but far more suspicion arose when Melba travelled across Europe to St Petersburg to sing for the Tsar: the Duke followed closely behind her on the journey across Europe, and they were spotted together in Paris, Brussels, Vienna, and St Petersburg, a succession of meetings no-one could believe to be coincidence; the news that the pair had been seen sharing a box at the Vienna Opera served as effective proof to all but the most innocent or forgiving. The journalists of the day being neither, the story was soon spread across the mainstream media. Charles Armstrong, angry and embarrassed at being so publicly cuckolded (Melba and he were still legally married), filed divorce proceedings on the grounds of Melba's adultery, naming the Duke as co-respondent; he was eventually persuaded to quietly drop the case, but the damage was done, and the Duke decided that a two-year African safari (naturally, sans Melba) would be appropriate. He and Melba did not resume their relationship, Melba having decided - or having been forced to decide by the circumstances - that discretion, and the attendant loneliness, were necessary if she were to maintain her position. Her marriage to Armstrong was finally terminated when, having emigrated to the United States with their son, he divorced her in Texas in 1900.[4][5]

Career

Débuts at Brussels, London and Paris

Having established herself on the concert circuit in Melbourne,[6] in 1886 the chance to travel to Europe arose when her she travelled to London but was offered nothing by either Sir Arthur Sullivan or Carl Rosa.[7] She then went to Paris to study with the foremost teacher Mathilde Marchesi, and had her first starring role (as Gilda) at the Théâtre de La Monnaie, Brussels on 12 October 1887.[8] It was at this time, on Marchesi's advice, that she adopted the stage name of "Melba" - a contraction of the name of her native city.[9]

In that year (1887) Melba had her Covent Garden début, but made so little impression that they only offered her the role of Oscar for the next season there. Melba however persuaded the influential patroness Lady de Grey to adopt her cause, and returned instead as Donizetti's Lucia on 1 June 1888.[10] This was an immense success, and established her unshakeable influence over the theatre's management over the next four decades.[11]

Her opening success in Paris was as Ophélie in Hamlet by Ambroise Thomas,[8], outshining most of her predecessors in this role created in the 1860s by Christina Nilsson. Back in London she appeared opposite Jean de Reszke in Roméo et Juliette (June 1889), and she was then in Paris as Marguerite, Juliette, Ophélie, Lucia and Gilda.[8]

Consolidation

Thus began a professional career in Australia, England, Europe and the United States that saw her as the prima donna at Covent Garden through to the 1920s. She was feted by royalty and her recordings for HMV always cost at least one shilling more than any other singer's, having their own distinctive mauve label as well. Before the First World War, Melba nights were social events and the audience blazed with jewels. Melba herself wore couture costumes by Worth of Paris and her own jewels. The Performing Arts Collection in Melbourne holds a cloak made for Melba to wear in Lohengrin, which she had to rescue from the Russian border guards, despite the fact that she was travelling for a command performance to the Tsar. The Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, has a less glamorous velvet dress worn in Faust. The Metropolitan Opera Collection has her pink enamel and diamond Fabergé parasol handle, and the State Library of New South Wales holds a gold, diamond and jade Cartier pinbox presented to her when she was made a Dame in 1918. Melba also sang in New York at the Met and Chicago, and famously, at Oscar Hammerstein's opera house, drawing the Met audiences to his new theatre, even though Enrico Caruso was singing at the Met. She rescued the house financially.

Melba visited New Zealand in February 1903 after her tour of Australia. She arrived in Invercargill from Hobart and was welcomed by the Prime Minister Sir Joseph Ward and Lady Ward.[12] After giving one concert in Dunedin she travelled to Christchurch[13] and gave a concert in Wellington.[14] She also undertook strenuous tours of small Australian country towns where she would often perform only in a wooden hall, like the Prince of Wales Opera House in Gulgong. The concerts were sold out and the windows were left open, partly because of the heat and partly because Melba wanted Australians to hear her. Many even listened from underneath the floor, the halls being built up off the ground and the wooden structure providing excellent acoustics. Her attitude to these concerts and the audiences attending was summed up in her advice to Clara Butt, when the contralto was planning a similar Australian tour: "Sing 'em muck - it's all they understand!" To another colleague and compatriot, Peter Dawson, she described his home city of Adelaide as "that city of the three P's— Parsons, Pubs and Prostitutes." [15]

In order to increase her fees, she took the highly entrepreneurial step of ostentatiously moving to a hotel in Monte Carlo in the hope that the engaged prima donna would fall ill and that she would be asked to substitute, at a high fee.[16] Her total savings at that time were just £400 and she was at one point "feeling desperate". This proved successful, and in 1904 she sang the title role in the world premiere of Camille Saint-Saëns's Hélène at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo. Despite her fame, and her studies with the great composers of the day such as Charles Gounod, the only other role created by her was Elaine by Herman Bemberg (Giacomo Puccini wrote the role of Cio Cio San with Melba in mind, but she never sang it).[17] She was, however, the first to sing the role of Nedda in Pagliacci in London in 1892 (soon after its Italian premiere), and in New York in 1893. In this year her first tour of the United States had to be postponed for a week as King Oscar II of Sweden had requested an unscheduled Royal command performance before she left. King Oscar had been so excited by her previous performance that he had stood twice, forcing the audience to stand also in the middle of the opera. Melba was also the first to sing Mimi in Puccini's La bohème in New York.

Honours

She was appointed Dame Commander of the British Empire in 1918 for her charity work during World War I, and was elevated to Dame Grand Cross of the British Empire in 1927. She and Dame May Whitty were the first entertainers to be awarded the honour of Dame Commander of the British Empire.

Melba was the first Australian to appear on the cover of Time magazine, in April 1927.[18] She was selected to sing the then national anthem, God Save the King, at the official opening of the Parliament House in Canberra, on 9 May 1927, the day on which Canberra became Australia's capital city.

Legends and anecdotes

Melba was known for her demanding, temperamental diva persona. John McCormack, on the night of his London debut, attempted to take a bow with her on stage, but she pushed him back forcefully, saying "In this house, no one takes a bow with Melba." When recording with lesser studio artists, she would never try to hide her contempt for them, once dismissing tenor Ernest Pike as "one of the bloody chorus".[15] She enjoyed singing with Enrico Caruso, but considered him coarse and uncultivated; he would play practical jokes on her, on one occasion - whilst singing the Puccini aria Che Gelida Manina ("Your Tiny Hand is Frozen") - pressing a hot sausage into her hand. She jealously guarded her position as prima donna, in the process earning both the enmity and the awe of many colleagues. Emma Eames' memoirs describe Melba as a wicked force who frustrated opportunity after opportunity for Eames; Eames also averred that when playing Marguerite in Gounod's Faust, Melba, when singing the jewel song, "would have hung the jewels off her nose if she could!" Titta Ruffo, Rosa Ponselle, McCormack, Luisa Tetrazzini, Frances Alda, and others also described their unpleasant experiences with Melba. Mary Garden, another rival, wrote "I never saw such a fat Mimì in my life. Melba didn’t impersonate the role at all – she never did that" (Melba's dramatic skills were once described as being limited to indicating emotion by raising one arm - and indicating great emotion by raising both); but continued, "but, my God, how she sang it."[17]

Patronage of others

Despite the antipathy and dislike Melba inspired in many of her own peers, she did help the careers of younger singers. She taught for many years at the Conservatorium in Melbourne and looked for a "new Melba". She thought she had found such a person in Stella Power (1896–1977), an Australian lyric soprano, whom Melba herself trained at the Albert Street Conservatorium, East Melbourne. Power, whom Melba herself dubbed "The Little Melba", sang in her first engagement in 1916, and proceeded to sing across the world and record; but by the mid-1920s, her career had stalled, and she was reduced to singing in picture-palaces and in popular revues.

Others also benefited from Melba's praise and interest. She passed her own personal cadenzas onto a young Gertrude Johnson, a valuable professional asset. In 1924, Melba brought the new star Toti Dal Monte, fresh from triumphs in Milan and Paris but still unheard in England or the United States, to Australia as a principal of the Melba-Williamson Grand Opera Company. After sharing the Covent Garden stage in a 1923 night of operatic extracts with her fellow Australian soprano, Florence Austral (who, as a dramatic soprano, posed no threat to Melba the lyric soprano), Melba was fulsome with her praise, describing the younger woman as "one of the wonder-voices of the world";[19] the American contralto Louise Homer she described as possessing "the world's most beautiful voice". The Australian painter Hugh Ramsay, living in poverty in Paris, was given financial assistance by Melba, who also helped him to forge connections in the artistic world.[17] The Australian baritone John Brownlee and tenor Browning Mummery were both proteges: both sang with her in her 1926 Covent Garden farewell (recorded by HMV), and Brownlee accompanied her on two of her last commercial recordings later that year (a session arranged by her in part to promote Brownlee). The "Dite alla giovane" from Traviata is especially beautiful with its unique plunge on "raggio". Not the least of those whom she assisted was Puccini himself, whose works were given greater public promenance by her enthusiasm, for La Bohème in particular - following a poor reception at its British premier in Manchester in 1897, it was Melba who bullied the Covent Garden management into producing it during the 1899 season.[17]

Others were not so fortunate. Melba had been open in admiring her fellow-Australian Florence Austral in 1923, when Melba was still performing at Covent Garden, and Austral firmly established in very different repertoire; when, however, a young, 19-year old Australian soprano sought out Melba in 1928, hoping for an audition, from which might follow advice or assistance, Melba - by now winding down her career - refused the requests, unwilling to acknowledge or assist another Australian who might eclipse her in fame and popularity. Ironically, the younger woman, Marjorie Lawrence, would become as firmly established in the Wagnerian canon as Austral.

Melba served as Patroness (President) of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra from 1921–1932.

Radio performances

In June 1920 she was heard in a pioneering radio broadcast from Guglielmo Marconi's factory in Chelmsford, England, singing two arias and her famous trill. Radio enthusiasts across the country heard her, and the broadcast was reportedly heard from as far away as New York. People listening on the radio barely heard a few scratches of the trill and two arias she sang. Further radio broadcasts would include her Covent Garden farewell performance, and a 1927 Empire Day broadcast (broadcast throughout the British Empire, by radio station 2FC, Sydney, on Monday 5 September 1927; it was relayed by the BBC London on Sunday 4 September).[20]

"Farewells"

She then left for Europe and later developed a fever in Egypt which she never quite shook off. She is also well remembered in Australia for her seemingly endless series of "farewell" tours between her last stage performances in the mid 1920s and her final, last concerts in Australia in Sydney on 7 August 1928, Melbourne on 27 September 1928 and Geelong in November 1928.[1] The real final performance was a mere matinee of La bohème in Adelaide. From this, she is remembered in the vernacular Australian expression "more farewells than Nellie Melba".

Her autobiography "Melodies and Memories" was published in 1925. There are several full-length biographies devoted to her, especially those of Hetherington, Therese Radic and, most recently (2009), Ann Blainey. Countless monographs, magazine articles and newspaper stories have been devoted to her, too. A motion picture called "Evensong" (1934) was a loose adaptation of her life based on the book by Beverley Nichols, and voiced by Conchita Supervia, a mezzo singer most unlike Melba. In 1946–1948 the ABC produced a popular radio series on Melba starring Glenda Raymond, who became one of the foundation singers of the Australian Opera (later Opera Australia) in 1956. Later the Australian Broadcasting Commission produced a more authentic mini-series on her life "Melba" (1987), starring Linda Cropper miming Yvonne Kenny, which does not quite convey the more exciting side to her story.

Death

She returned to Australia but died in St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney in 1931, aged 69, of septicaemia which had developed from facial surgery in Europe some weeks before.[1] The evidence for the facelift being the cause has been doubted in the latest biography of Melba; the timeline of five months between operation and hospitalization makes this causation unlikely. The fever she had caught in Egypt on the way home, however, probably led to the blood poisoning. She was given a state funeral from Scots' Church, Melbourne, which her father had built and where as a teenager she had sung in the choir.[1][21] The funeral motorcade was over a kilometre long, and her death made front-page headlines in Australia, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Europe. Billboards in many countries said simply "Melba is dead". Part of the event was filmed for posterity. Melba was buried in the cemetery at Lilydale, near Coldstream. Her headstone bears Mimi's farewell words: "Addio, senza rancor" (Farewell, without bitterness).

Recordings

Melba's first recordings were made c.1895-96, recorded on cylinders at the Bettini Phonograph Lab in New York. A reporter from Phonoscope magazine was impressed - "The next cylinder was labelled ‘Melba’ and was truly wonderful, the phonograph reproducing her wonderful voice in a mar vellous manner, especially the high notes which soared away above the staff and were rich and clear." Melba was less impressed- "Never again, I said to myself as I listened to the scratching, screeching result. Don’t tell me I sing like that, or I shall go away and live on a desert island." The recordings never reached the general public - destroyed on Melba's orders, it is suspected - and Melba would not venture into a recording studio for another eight years.[22]

Melba can be heard singing on several Mapleson Cylinders, early attempts at 'live' recording, made by the Metropolitan Opera House librarian Lionel Mapleson in the auditorium there during performances. These cylinders are often poor in quality, due to the inherent nature of the early recording process, the placement of the equipment (particularly poor in the case of those Melba is heard in), and repeated playings of favourite cylinders by Mapleson over many years; they do, however, preserve something of the quality of the young Melba's voice and performance that is sometimes lacking from her commercial recordings. Ironically, the cylinder she is most renowned for, Queen Marguerite's cabaletta from Les Huguenots, may not in fact feature her, but rather her contemporary Suzanne Adams: the sonics of the recording do not match others of the same year, and the paper evidence points to Adams; but the singer sounds more like the Melba rather than the Adams both known from their commercial recordings.[23]

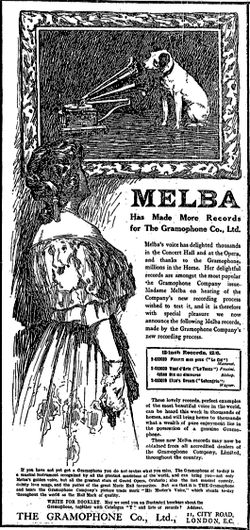

Melba made numerous gramophone (phonograph) records of her voice in England and America between 1904 (when she was already aged in her 40s) and 1926 for the Gramophone & Typewriter Company and the Victor Recording Company. Most of these recordings, consisting of operatic arias, duets and ensemble pieces and songs, have been re-released on CD for contemporary audiences. Melba had been persuaded back into the studio by G&T, who applied the persuasions of Landon Ronald and Camille Saint-Saens, and demonstrated to her through the playing of records of Caruso that recording was now improved enough to set down a life-like account of a singer's voice.

The poor audio fidelity of the Melba recordings reflects the limitations of the early days of commercial sound recording. Melba's acoustical recordings (especially those made after her initial 1904 session) fail to capture vital overtones to the voice, leaving it without the body and warmth it possessed - albeit to a limited degree - in life. Despite this, they still reveal Melba to have had an almost seamlessly pure lyric soprano voice with effortless coloratura, a smooth legato and accurate intonation. Melba had perfect pitch and critic Michael Aspinall says of her on the complete London recordings issued on LP, that there are only two rare lapses from pitch in the entire set. Even so they are hard to hear. The recordings give an idea of the voice which people described as silvery and disembodied, with the notes forming in the theatre as if by magic and floating up through the theatre like a floating star. Like Adelina Patti, and unlike the more vibrant-voiced Luisa Tetrazzini, Melba's exceptional purity of tone was probably one of the major reasons why British audiences, with their strong choral and sacred music traditions, idolised her.[24]

Melba's official "farewell" to Covent Garden on 8 June 1926, in the presence of King George V and Queen Mary, was recorded by HMV, as well as broadcast. The programme included Act 2 of Roméo et Juliette (not recorded because Charles Hackett was not under contract to HMV), followed by the opening of Act 4 of Otello (Desdemona's "Willow Song" and "Ave Maria") and Acts 3 and 4 of La bohème (with Aurora Rettore, Browning Mummery, John Brownlee and others). The conductor was Vincenzo Bellezza. At the conclusion Lord Stanley of Alderley made a formal address and Melba gave her (tearful) farewell speech. In a pioneering venture, eleven sides (78rpm) were recorded via a landline to Gloucester House (London), though in the event only three of these were published. The full series (including both speeches) was included in a 1976 HMV reissue. Despite the technical inadequacy of these early electric 'live' recordings, they bear witness to the lovely and unimpaired quality of her voice, even if her breath support was not what it had formerly been.[25]

As was the case in many of her performances, most of Melba's recordings were made at 'French Pitch' (A=435 Hz), rather than the British early 20th century standard of A=452 Hz, or the modern standard of A=440 Hz. This, and the technical inadequacies of the early recording process (discs were frequently recorded faster or slower than the supposed standard of 78rpm, whilst the conditions of the cramped recording studios - kept very warm to keep the wax at the necessary softness when cutting - would wreak havoc with instrumental tuning during recording sessions), means that playing her recordings back in the speed and pitch she made them at is not always a simple matter.

Legacy

Coldstream

In 1909, she bought property at Coldstream, a small town 50 km east of Melbourne and around 1912 had Coombe Cottage built. The house is located at the current juncture of Maroondah Highway and Melba Highway (named in her honour). Coombe Cottage is now the residence of Melba's granddaughter, Pamela, Lady Vestey (the mother of the 3rd Lord Vestey). Melba also set up a music school in Richmond, which she later merged into the Melbourne Conservatorium.

Melba became associated with the song "Home sweet home". She inherited it from Adelina Patti as Prima Donna Assoluta and after many performances the piano would be wheeled out and she would accompany herself singing the song, so bittersweet for her as home was an 11,000 mile sea voyage away when in England. Joan Sutherland later continued the tradition of singing "Home sweet home" and sang it after her own farewell performance in Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots at the Sydney Opera House in 1990.

Melba, the last of the 19th century tradition of bel canto sopranos, is one of only two singers with a marble bust in the foyer of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. The other is Adelina Patti. Sydney Town Hall has a marble relief bearing the inscription "Remember Melba", unveiled during a World War II charity concert in memory of Melba and her World War I charity work and patriotic concerts. Melba was closely associated with the Melbourne Conservatorium, and this institution was renamed the Melba Memorial Conservatorium of Music in her honour in 1956. The music hall at the University of Melbourne is known as Melba Hall.

In 1953, Patrice Munsel played the title role in Melba, a biopic about the singer.

The suburb Melba, Australian Capital Territory is named after Nellie Melba. All the streets are named after composers, singers and other musically notable Australians.

The current Australian 100 dollar note features the image of her face.

'Melba' House at the school Melbourne Girls College in Richmond, Melbourne, uses her name to remember a strong feminist set on leading and achieving.

Her name is associated with four foods, all of which were created by the French chef Auguste Escoffier:

- Peach Melba, a dessert

- Melba sauce, a sweet purée of raspberries and redcurrant

- Melba toast, a crisp dry toast

- Melba Garniture, chicken, truffles and mushrooms stuffed into tomatoes with velouté.[26]

Film

In 1953 a biopic entitled Melba was released. It was produced by Horizon Pictures and directed by Lewis Milestone. Nellie Melba was played by Patrice Munsel.[27]

Appearances in fiction

Melba makes an appearance in the 1946 novel Lucinda Brayford by Martin Boyd. Melba attends a garden party thrown by Julie and Fred Vane, mother of the eponymous heroine: "Melba sang two or three songs, Down in the Forest, Musetta's song from Boheme, and finally Home, Sweet Home. She is described as having the "loveliest voice in the world".[28]

See also

- Eva Mylott

- Landon Ronald

- 2MT

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Jim Davidson (2006). "Melba, Dame Nellie (1861 - 1931)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, Online Edition. Australian National University. http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A100464b.htm. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ↑ Bruce McPherson (2002). "History of the Ann Street Presbyterian Church". annstreetpcq.org.au. Ann Street Presbyterian Church. http://www.annstreetpcq.org.au/churchhistory.html. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ↑ The Record Collector, vol 54(4) p294

- ↑ The Times ( 5 November 1891): 5, ( 6 November 1891): 9, ( 20 February 1892): 5, ( 17 February 1892): 13, ( 12 March 1892): 16, ( 14 March 1892): 3, ( 24 March 1892): 3.

- ↑ http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A100464b.htm

- ↑ Blainey, 2008

- ↑ Scott, 1977, p. 28

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Eaglefield-Hull, 1924

- ↑ As was the case of Florence Mary Wilson, named Florence Austral and Elsie Mary Fischer renamed as Elsa Stralia; (both named after Australia). June Mary Gough was named June Bronhill (after Broken Hill).

- ↑ Scott, 1977, p. 29

- ↑ Scott, 1977, p. 29

- ↑ Otago Daily Times, 17 February 1903, p. 6

- ↑ The Press, February 20, p.5

- ↑ Evening Post, 24 February 1903, p. 5

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 http://www.gramophone.net/Issue/Page/January%201949/3/863056/#header-logo

- ↑ The Past Revisited by Marie Galway p. 217

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 http://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:UlGZU5pgBJIJ:www.peterbassett.com.au/PDFs/Melba.pdf+marjorie+lawrence+melba&hl=en&gl=uk&pid=bl&srcid=ADGEESisT4vigcPZXphpNbgX84iu-PRwIIyfdBIuRGH1LbtToHhEnShgGRS-4RlJIMr-vu-z-jrB9hKlOxKXoNVeLgdt6iAl1u1Lt44z75fGM52z3pAmF8E-V8kUiXvwaMw5KYniCFEu&sig=AHIEtbRyfafi9TQmVs2NhuHPe20M5J5GFQ

- ↑ TIME Magazine Cover: Nellie Melba - Apr. 18, 1927

- ↑ http://www.bikwil.com/Vintage10/Florence-Austral.html

- ↑ First Empire Broadcast, held by the National Library of Australia

- ↑ "Church History". Scots' Church website. Scots' Church. 2010. http://www.scotschurch.com/church-history. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- ↑ http://www.historicmasters.org/?page_id=207

- ↑ http://oq.oxfordjournals.org/content/5/4/37.extract

- ↑ Recordings: From a Vault in Paris, Sounds of Opera 1907

- ↑ Aspinall 1976, pp.4, 15.

- ↑ Guardian, Famous Foodies: Nellie Melba

- ↑ Melba at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Lucinda Brayford by Martin Boyd, Lansdowne Press, p96, 1972 edition

Literature

- Michael Aspinall, Nellie Melba: The London Recordings 1904-1926, Insert booklet to HMV reissue LP set RLS 719 (limited edition), (EMI, London 1976).

- Ann Blainey, I am Melba Australian edn, (Black Inc. 2008); Marvelous Melba: The Extraordinary Life of a Great Diva, American Edition (Ivan R. Dee, 2009).

- John Frederick Cone, Oscar Hammerstein's Manhattan Opera Company (University of Oklahoma Press 1966)

- Arthur Eaglefield Hull, A Dictionary of Modern Music and Musicians (Dent, London and Toronto 1924).

- Emma Eames, Some Memories and Reflections (D. Appleton & Co., 1927).

- John Hetherington, Melba, a Biography (Faber and Faber, London 1967). (Contains extensive bibliography)

- Nellie Melba, Melba Method (Chappell, London & Sydney 1926).

- Agnes Murphy, Melba: A Biography (Chatto & Windus, London 1909).

- George Bernard Shaw, Music in London (Constable, London 1931-33).

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Armstrong, Helen Porter". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. http://gutenberg.net.au/dictbiog/0-dict-biogA.html#armstrong1.

External links

- Biography at Australian Dictionary of Biography online

- The Melba Collection - Audio, video, images and text from the Victorian Arts Centre in Melbourne

- International Jose Guillermo Carrillo Foundation - digitally remastered MP3 files from Melba's recordings 1905-1910.

- The Reserve Bank of Australia page on Melba

- Dress worn by Dame Nellie Melba

- Nellie Melba - includes her 1906 recording of the Aubade from the opera by Edouard Lalo Le Roi d'Ys (1888)

- Nellie Melba at the National Film and Sound Archive